| N |

| A |

| D |

| G |

| L |

| 24 |

| I |

| V |

If you would really like to learn dialects spoken in Croatia, a separate course or textbook would be needed. So far, nobody has written something like it, but it can be done. (Maybe I’ll find some time one day?) Consider this a lightweight overview.

Do you need traditional dialects? Essentially, no. But you’ll maybe hear some song in a dialect, or read a book which has some dialogues in a dialect. Or you maybe have a personal interest because your family comes from an area where a dialect is spoken.

For a long time, there was a general idea that only one dialect in Croatia is ‘proper’. There were literary works in other dialects, but they were mostly poetry and had a little influence. Children were discouraged from using their native dialects at school by most (but not all) teachers. So it seemed dialects were destined for oblivion. For reasons which aren’t completely clear, in mid 1960’s there was a kind of revival of traditional dialects in Croatia (there was another wave in 1990’s, which will be covered in the next chapter). A part of that revival was a music festival in Krapina, a town northwestern from Zagreb, dedicated to songs in the local dialect.

On a cold Sunday morning back in December of 1968, Ana Bešenić, a scared, modest and cold 15-year-old high school student from Petkovec, a small village near Varaždinske Toplice, north from Zagreb – from a home with only one lightbulb, turned off early each evening to save money – rang on the door of the home of composer and singer Zvonko Špišić in Zagreb. She told him she wrote some verses for the festival. He almost sent her home, but after reading the verses, he decided to write a tune; together, they adapted the verses a bit, and the song was performed in Krapina, by Vice Vukov, then a very popular singer. The song starts with this verse:

V jutro dišeče gda bregi su spali

a mesec još zajti ni štel

potiho sem otprl rasklimanu lesu

i pinklec na pleča sem del

It’s hopeless to look into almost any Croatian dictionary. You could ask someone who natively speak that dialect, or someone who at least understands words in this song. Luckily for you – everyone in Croatia understands these words, as the song became immediately very, very popular. Sung by professional singers, sung by common people in house parties, sung around campfires – sung even by some enthusiasts learning Croatian – it kind of became a folk song. We can start understanding it by explaining the verbs from the lines above:

|

deti (dene) perf. put dišati (diši) smell (pleasantly) otprti (otpre) perf. open |

spati (spi) sleep šteti (hoče) want |

Note that spati (spi) sleep feels archaic in most parts of Croatia today, but the verb zaspati (zaspi) inch. fall asleep was clearly derived from it many centuries ago.

These verbs have a bit specific forms:

dojti (dojde, došel, došla) perf. come

najti (najde, našel, našla) perf. find

zajti (zajde, zašel, zašla) perf. set (Sun and Moon)

The corresponding standard verb forms would be doći (...), naći and zaći. These dialects are among ones preserving older forms of these verbs (mentioned in the section Something Possibly Interesting in the chapter 42 Come In, Come Out, Go.)

The adjective dišeči is the present adjective of dišati (diši), so it means pleasant-smelling, i.e. fragrant.

The lines above translate as:

In a fragrant morning, [when hills were sleeping

And the Moon still didn’t want to set]

I quietly opened the rickety gate

And put the bag on my back

This song – Suza za zagorske brege A Tear for Zagorje Hills – is usually considered one of the greatest Croatian songs. Like a lot of very popular Croatian songs, it’s not in Standard Croatian. The song goes on:

Stara je mati išla za menom

nemo vu zemlu gledeč

Ni mogla znati kaj zbirem vu duši

i zakaj od včera nis rekel ni reč

In that dialect, instead of lj, there’s usually l: zemla ground, earth, country instead of zemlja, prijatel friend instead of prijatelj.

We also find some specific forms of the present tense of the verb be:

| biti be | this dialect | standard |

|---|---|---|

| pres-1 | sem² | sam² |

| neg. pres-1 | nis | nisam |

| neg. pres-3 | ni | nije |

Almost immediately later, we have a line:

v suzah najenput sem bil

So, if v¨ is in – and it is – what’s the form suzah? It looks like a case of suza tear, we assume he was in tears, but what’s that case?

This is the locative case. In this dialect – and actually, in many old dialects – cases D, L and I are distinct in plural and have special, so-called older endings:

| suza tear | older | standard |

|---|---|---|

| D-pl | suzam | suzama |

| L-pl | suzah | |

| I-pl | suzami |

(These endings are really older than the standard endings; Slovene, Russian and Polish have such endings.)

To help you decipher these two cases in chapters about dialects, they will be highlighted with different colors: light green for L and green for D, if you place your mouse over an example sentence – or touch it, if you use a touchscreen. Moving your mouse (or touching somewhere else) will remove the highlight.

In real life, some local dialects have slightly different endings, approaching standard ones. Many people mix their dialect and the standard language, so you’ll often see a mixture of endings. For example, a few lines later, we have (the preposition z¨ corresponds to both standard s¨/sa and iz¨; here it means with because it’s followed by I):

z rukami lice sem skril

This is one of the saddest lines in any Croatian song – he hid his face with his hands so that his mother couldn’t see he’s crying – and it’s also the line which was originally sung by Vice Vukov as z rukama, i.e. with the standard I-pl ending. However, all modern performances by bands using traditional instruments, and almost all other modern performances use the more characteristic z rukami with hands. (More about this song in the Examples section below.)

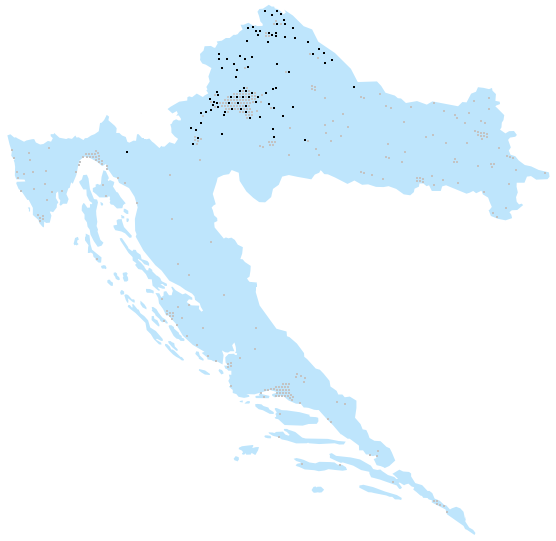

The song is in a dialect traditionally called ‘Kajkavian’. These dialects are named after the pronoun kaj what (compare it to the standard Croatian što). The colored areas on this rough map have (or had until very recently) this word for what in the local speech (or a very similar word):

The darker area is roughly where, besides the word kaj, there’s another feature: the word for wind has two same vowels, it’s veter ▶ . Many other words have e where there’s a in standard Croatian in the whole kaj-area, such as megla fog, pes dog, steza path, and so on, but the same vowels in veter are specific for the darker areas. (Only a small number of these features appear in Zagreb speech today, due to immigration from other areas and influence of Standard Croatian.)

The darker area dialects have many interesting features and they could be considered a language on their own (actually, most dialects in Croatia can be considered languages – the difference is only in their social and political status; such issues will be explored later). An obvious feature is, of course, the word kaj what, and words derived from it:

|

nekaj something nikaj nothing | zakaj why |

Another characteristic is the negative present tense of the verb moći (...) can; instead of e.g. ne može, it’s only one word: pres-3 is nemre, and it changes like a regular verb! Then, the future tense is formed with the present of the verb (bude) and the past form of the verb, but the verb (bude) has additional, shortened present tense forms. This table lists both verbs in the present tense:

| pers. | (bude) | moći (...) | ne + moći (...) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | bum | morem | nemrem | |

| 2 | buš | moreš | nemreš | |

| 3 | bu | more | nemre | |

| 1-pl | bumo | moremo | nemremo | |

| 2-pl | bute | morete | nemrete | |

| 3-pl | buju | moreju | nemreju |

The pres-3pl ending of moći is -eju, compared to standard Croatian -u. This applies to other verbs with pres-3 in -e as well.

Another feature – you’ve likely already guessed it – the past-m ending for verbs is simply -l, which makes verb forms more regular than in Standard Croatian; for example, it’s just bil, bila...

There are also some specific forms of pronouns in the instrumental case:

| pers. | ‘Kajkavian’ | standard |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (z) menom | (sa) mnom |

| 2 | (s) tebom | (s) tobom |

Why the form sem² instead of sam²? Why e in rekel vs rekla? Why veter? To answer these questions, another bit of history:

Roughly 1100 years ago, before any of the today dialects (some of which were later used as languages) in the Slovenia-to-Serbia area were differentiated, there was yet another vowel, which can be written as ə. For example, the pres-1 of biti be was səm², while the word for wind was větər. Many words had this vowel: pəs dog, kəsno late, tənək thin, məgla fog, stəza path, dənəs today etc. The past-m of reći perf. say was rekəl. We don’t know how ə was exactly pronounced (and it likely varied by region) but we’re sure it existed, since old writings have a special letter for it.

And then, in many dialects, the system got simpler. The vowel ə merged with other vowels, but it happened differently in different regions. In most dialects, it changed to a, but in the area around today Zagreb it changed to ě.

So after ə was gone, we had ě left, precisely the vowel that changed into either a plain e (giving rise to the ‘Ekavian’ prounciation), or i (in ‘Ikavian’ areas), and even into either ije or je. The last option happened in parts of Croatia and Bosnia, and that was taken as the basis of Standard Croatian.

But something else happened in the darker area: there ě usually has remained a separate vowel to this day. The word for wind there is actually větěr (the unstressed ě is often pronounced like e in English the), while e.g. the e in the word pet five is pronounced somewhat like a in English bad or e in English bed.

To illustrate this, here are these two words pronounced by a native speaker from a village short drive north from Zagreb:

| pet ▶ five | větěr ▶ wind |

Unfortunately, these two sounds are often spelled the same, and that gives the impression that ‘Kajkavian’ is ‘Ekavian’, but it’s not. (‘Kajkavian’ in towns such as Zagreb, Samobor and Varaždin was really ‘Ekavian’, but villages kept the older system.) Generally, these dialects have more vowels than Standard Croatian. Most of them distinguish short from long vowels, and in some dialects (roughly in the central Zagorje region) certain long vowels are pronounced as diphtongs (e.g. like English so, lake, etc.). Here are some examples:

diěte

▶

child (spelled dijete, pronounced djete)

meese

▶

meat (meso)

rouka

▶

hand (ruka)

suonce

▶

sun (sunce)

So, in this very dialect (examples are from a village in central Zagorje, near Zlatar) long ě is pronounced as iě, and sometimes written so. For comparison, forms spoken in Zagreb are given in brackets. In the word for meat, there’s simply a long e, which I spelled as ee.

Although many ‘Kajkavian’ dialects have such diphtongs, I’ve never heard a popular song in that dialect – they are likely considered too strange for outsiders.

Another interesting thing in some dialects (including this) is that regular neuter nouns and adjectives – like the word for meat – end in -ě or -e, and not in -o.

Futhermore, in ‘Kajkavian’ dialects (including the dialects in Slovenia) there’s one important constraint: normally, only stressed vowels can be long, i.e. there are no unstressed long vowels, while stressed vowels can be either long or short. Since the vowel length and stress often changes according to the word form (i.e. gender, case), this produces many alternations:

doběr (m) vs. duobra (f) good

rouka (N) vs. rukami (I-pl) hand

In the first word, the vowel lengthened in feminine because the short ě was lost; in the second, ou shortened because the stress moved to another syllable (note that this shift apparently doesn’t happen in the dialect of Suza za zagorske brege). As you can see, the system is far from trivial, and there are many local variations.

While there are more vowels than in standard, there are fewer consonants – no dž, no ć and usually no đ; some cluster are simplified, instead of e.g. svi all (people), the shorter si is used.

I haven’t answered why the word kaj in that area. Nobody knows.

Back to songs! Soon after the Tear, there was another song, just a bit less popular:

Dobro mi došel prijatel

vu stari zagorski dom

budi kak doma vu vlastitoj hiži

tu pri pajdašu si svom

We encounter the word hiža, meaning house. The fourth line has an interesting construction:

pri + D = std. kod¨ + G

Compare it with the standard verb prići come close, approach which also uses D (the verb is priti (pride, prišel, prišla) in this dialect, of course). The song continues:

Vre je stara hiža ova

al još navek tu stoji

nemreš srušit ovog krova

taj se ničeg ne boji

You’ve probably noticed the pres-2 form nemreš and interesting stress in present tense forms of some verbs: stoji he/she/it stands and boji se² he/she/it is afraid. Such stress is impossible in standard Croatian, but it can be guessed from it: verbs which have an underline – i.e. the fixed stress – in present tense forms in the standard stress scheme will have fixed stress one one syllable to the right in this (and many other) dialects:

| standard | “old” dialects | |

|---|---|---|

| be afraid | boji se² | boji se² |

| hold | drži | drži |

| stand | stoji | stoji |

‘Kajkavian’ dialects often conserve older forms of some words, such as some words starting with cr- in Standard Croatian:

| standard | ‘Kajkavian’ | |

|---|---|---|

| intestines, hose | cr |

črěvo, čriěvo etc. |

| black | crn | črn |

| worm | crv | črv |

A lot of words used in ‘Kajkavian’ are not heard in Standard Croatian or are very rare; for example, this verb pair:

hitati (hiče) ~ hititi throw

A couple of very characteristic ‘Kajkavian’ verbs are:

|

děti (děne) perf. put peti go, drive |

povědati tell, speak zeti (zeme) perf. take |

Some verbs have a different (but obviously related) meanings in comparison to the standard language:

běžati (běži) run

Some verbs differ just a bit; a common variant is:

opasti (opadne, opal) perf. fall

There are a number of specific constructions and phrases, a quite common one is:

imati + rad(a) + A = love

Here, rad is an adjective, a secondary predicate precisely (like sam alone, on their own) and takes different forms depending on the gender of the subject. (For another characteristic construction, check the Examples section.)

Unfortunately, it would be too much to go over all ‘Kajkavian’ characteritics, as a whole book could be written...

While Zagreb is generally shown as ‘Kajkavian’ on dialect maps, you’ll basically never hear stoji in Zagreb, except from people from some village who came to visit the city. Today, the speech of Zagreb has the following characteristics (some of them, like di, are not generally ‘Kajkavian’):

| Features in Zagreb speech today | |

|---|---|

|

common ↑ ↓ very rare | ‘western pronunciation’ |

| di where kaj what, zakaj why... neg. pres-3 of can: nemre |

|

| forms bum, buš... | |

| past-m forms in -l, words like pes | |

| zeti (zeme) perf. take, menom (I of ja) | |

| deca children, steza path, megla fog... | |

Another very frequent feature in Zagreb are shortened adverbs and conjunctions, e.g. ak if (vs. standard ako), tam there (vs. standard tamo), kam where to (vs. standard kamo), etc.

Some ‘Kajkavian’ characteristics are preserved only in set phrases, usually conserved in songs, in decorative texts, etc., such as Zagreb, tak imam te rad (i.e. Zagreb, I love you so much). Try to Google™ it!

Another thing that varies among speakers in Zagreb is stress, especially in some nouns. For example, these nouns have traditionally stress on the second syllable in the traditional speech in Zagreb:

|

dvorište yard igračka toy |

lopata showel prašina dust |

However, these nouns are often pronounced in Zagreb with the stress on the 1st syllable (I do it too); besides, the traditional form of the first noun is actually dvorišče. There are more such nouns.

Soon after the Krapina festival was established, there were two TV series where ‘Kajkavian’ was mostly spoken: Mejaši, broadcast 1970, with 7 one-hour episodes (the word means people who share a meja border, i.e. neighbors), followed by Gruntovčani, broadcast 1975, with 10 one-hour episodes. It seemed ‘Kajkavian’ was going mainstream.

But, for some reason, it didn’t happen. Since 1980’s, no song performed in Krapina became really popular, and it’s hard to hear anything ‘Kajkavian’ in Croatian media today – even on the radio station called Kaj. Many people in Croatia still speak various ‘Kajkavian’ dialects in their daily life, but it’s hard to estimate how many; we can assume most people in rural ‘Kajkavian’ areas use it, but only a part of people living in larger cities. If we overlay black dots over our standard population map (where each dot represents 10,000 people), we get a picture like this:

There are some 90 black dots, which translates to roughly 900 thousands speakers, give or take (it all depends on the estimate of ‘true Kajkavian’ speakers left in Zagreb, mainly older people or people who came from the surrounding areas). This is a lot for Croatia. This is roughly the population of Dalmatia.

If so, why is there so little ‘Kajkavian’ in public, especially in comparison with an endless stream of ‘Ikavian’ songs from Dalmatia? It’s not easy to answer, and a part of the answer is in political events of the 19th century, which will be covered a bit later.

Interesting stuff! Regarding your Something Possibly Interesting section, I think that your claims about the Slovene border could use some additional clarifications. While historically, the south Slovene dialect groups (namely the Littoral, Lower Carniolan, and Panonian) and their "cross-border" counterparts (Istrian Čakavian, Kajkavian) could be analyzed as having once had an uninterrupted dialect continuum, the border has been there more or less in its current form for hundreds of years at this point, and as such has caused some significant divergence between the "sister" dialects, although there are still many undeniable similarities at least at first glance. I agree that it's a travesty that this relationship is under-researched, and I'm aware of only one work on this topic:

ReplyDeletehttps://www.academia.edu/34989815/The_Position_of_Kajkavian_in_the_South_Slavic_Dialect_Continuum_in_Light_of_Old_Accentual_Isoglosses

Another slightly interesting thing: The White Carniola dialect in south-eastern Slovenia traces its origins at least partly to Štokavian through Vlach and Uskok migrations centuries ago. Nowadays, linguists treat it as a dialect of Slovene, and traditional songs from the region are included in the primary school curriculum. So every kid in Slovenia learns some (incomprehensible to them) songs in Štokavian Ekavian at some point :)