| N |

| A |

| DL |

| G |

| 24 |

| I |

| V |

This chapter will wrap up the remaining clauses and clause-like constructions, so it could be also called various stuff that can be done with da (and sometimes što).

The first thing we’re going to deal with are so-called complex conjunctions. Some clauses in Croatian can have two forms — one with što, and another with da. For example:

kao što (+ clause) as

kao da (+ clause) as if

The main difference is that forms with što refer to something that has happened, or will happen for sure (at least, what is expected to happen), and ones with da to something that did not happen, or is not expected to happen.

For example:

Vruće je° kao što je bilo prošli tjedan. It’s hot as it was the last week. ®

Vruće je° kao da smo u Africi. It’s hot as if we were in Africa.

The first sentence compares the heat to something that really happened, and the second one to something obviously not true. You can say the second sentence while in Africa only if you’re joking.

Another situation where we have što vs. da is with comparison conjunction nego, when used with a clause:

nego što (+ clause) than

nego da (+ clause) than (something imagined)

The combination nego da is only used to compare to something unreal, imagined, while nego što compares to another, existing action or state:

Hotel je bolji nego što sam očekivao. The hotel is better than I’ve expected. {m}

Another complex conjunction which shows such duality is umjesto:

(desired event) umjesto što (real event)

(real event) umjesto da (imagined event)

English here uses only instead.

When you look more carefully, the reason and purpose clauses follow a similar pattern:

zato što (+ clause) because

(zato) da (+ clause) so that

The correspondence is not perfect, for two reasons: first, zato is used in purpose clauses only for emphasis: only da is normally used. Second, purpose clauses are restricted to the present tense only.

Then, we have the word osim except ®, used in various complex conjunctions and similar stuff. They are:

osim ako unless

osim da/što except (see below)

osim...i... besides... also...

These constructions will be explained one by one. We will first tackle osim da and osim što. They are best understood as osim + clause. Which clause you’re going to use depends on the main verb.

For example, the expressions moguće je da... it’s possible that..., content clauses are used (the word moguć possible will be explained in 80 Present Adverbs and Adjectives). So, for example, you want to say that everything is possible, except that X. You would then use da, like in a content clause, and just add osim before it:

Sve je moguće, osim [da igram protiv Barcelone]. Everything is possible, except [‘that I play’ against Barcelona]. = except [me playing against Barcelona]

This is an actual translation of a statement by Andrés Iniesta I found on the Internet. Pay attention there’s no transformation in the Croatian sentence (from I play to me playing).

Recall that it’s common to use što to start a content clause when commenting on a fact (which is the subject then):

Dobro je [što pada kiša]. It’s good [it’s raining].

Next, we want to say it’s nice, except it’s raining:

Lijepo je° ovdje, osim

[što pada kiša].

It’s nice here, except [it’s raining].

In such cases, you have to use što.

The complex conjunction osim ako is quite different: it specifies a possible situation which will prevent the main clause (which is normally in the present tense or the future, but the meaning is future):

Ići ćemo na plažu, osim [ako će padati kiša]. We’ll go to the beach ‘except’ [‘if’ it rains]. = unless [it rains]

Like in other conditional sentences, use of tenses in much freer in Croatian.

However, there’s often ‘empty’ negation in such clauses, so this is actually more common:

Ići ćemo na plažu, osim [ako neće padati kiša]. (the same meaning!)

Remember: ‘empty’ negation after osim ako is optional. Negation after osim ako never has a really negative meaning.

Strictly speaking, these are conditional clauses, so the ‘potential’ future should be used with imperfective verbs, according to standard Croatian:

Ići ćemo na plažu, osim [ako bude padala kiša].

Ići ćemo na plažu, osim [ako ne bude padala kiša].

Such standard sentences have the same meaning as a bit colloquial ones with the common future tense, but they are significantly less common in real life (some 10 times less common on the Internet).

Then, osim... i... is used similar to English besides:

Osim sladoleda, nudimo i kolače. Besides ice-cream, we offer cakes as well.

Here the normal rules of osim + noun are observed (i.e. N, A → G). In writing, it’s common to use pored... i in this meaning as well.

The next thing is using da-clauses to express how something is done. Such clauses are then appended to tako so, in such way, so effectively we have tako da:

Odgovorite na pitanja tako da zaokružite broj ispred odgovora. Answer the questions ‘in such a way that’ you circle the number before the answer. (i.e. by circling a number)

There are two more constructions that use da-clauses. The first one corresponds to English construction too... to..., for example:

Goran je premlad [da vozi auto]. Goran is too young [to drive a car].

While English has too as a separate word, Croatian pre- is glued to the adjective (you will see it spelled separately from time to time, but it’s non-standard spelling).

While English uses a to-construction, Croatian sentences are of the desire type, i.e. only present tense (or conditional) but perfective verbs are allowed (one is used in the example below). Note that the Croatian construction is much more flexible, since anything can be a subject in the clause, while English is stuck with the infinitive, which cannot have a subject; therefore, English must use for when the subjects differ:

Sendvič je prevelik [da ga pojedem]. The sandwich is too big [for me] [to eat (it completely)].

Literally, the Croatian sentence says:

The sandwich is too big da I completely-eat it.

It’t interesting that in such sentences, conditional is used more often than the present tense; sometimes you’ll see the verb moći (može +, mogao, mogla) can also added to the clause, with not much difference in meaning (we now assume a male speaker, you’ll easily make examples for a female one):

Sendvič je prevelik [da bih ga pojeo].

Sendvič je prevelik

[da bih ga

mogaomoći

past-m pojesti].

As with other atemporal clauses, instead of biti (je² +) be, the verb (bude) should be used, but conditional prevails with that verb almost completely in this construction. This construction easily translates English phrases like too good to be true i.e. predobro da bi bilo istina – and similar – but they are not that common in Croatian and somehow always feel like translation of English phrases.

Another construction corresponds to English so... that... While the English construction looks quite different from the previous one, Croatian simply uses tako... da..., but the da-clause is of indicative-type (i.e. any tense, but no perfective verbs in present):

Knjiga je tako debela [da ću je čitati danima]. The book is so thick [that I’ll be reading it for days].

Besides tako so, you can use toliko so many (don’t forget it’s a quantity adverb, therefore, uncountable nouns have to be in G after it, and countable ones in G-pl):

Vidim toliko vrabaca

[da ih ne mogumoći

pres-1 izbrojati].

I see so many sparrows [that I can’t count them].

Sometimes toliko is used with adjectives, so you’ll encounter toliko skupa... da... and similar expressions:

Pizza je bila toliko ljuta [da sam popila litru vode]. The pizza was so hot [that I drank a liter of water]. {f}

(Croatian has one word for both angry and hot because of spices.) Besides these words, you can see takav (takv-) such, usually before nouns (but it can be used on its own, since it’s an adjective):

Magla je takva [da svi voze polako]. The fog is ‘such’ [that everyone is driving slowly].

(The last type, without a noun, must be slightly rephrased in English.)

This type of clause is sometimes called result clause; bear in mind that they require two things: a word like tako, toliko or takav (takv-) and an indicative da-clause.

In both English and Croatian, there’s also a third type, where the main verb is negated; in English not... such... to...:

Nisam takav idiot [da platim 1000 eura za to]. I’m not such an idiot [to pay 1000 euros for that].

Now the part after da is not going to happen, so both English and Croatian switch to an atemporal construction. We again see that Croatian clauses restricted to the present tense often correspond to English to-constructions. However, the clause in this construction can be also in the future tense or conditional:

Nisam tako glupa [da ću to kupiti]. I’m not so stupid [that I’m going to buy it]. {f}

Nisam tako glupa [da bih to kupila]. (the same meaning)

The last thing could be called the ‘weirdest construction’. It’s a kind of extension of the negative + nego construction, introduced in 43 And, Or, But: Basic Conjunctions. Recall:

To nije mačka, nego pas. It’s not a cat, it’s a dog. (or: instead, it’s a dog)

You can also say it for verbs:

On ne spava, nego gleda televiziju. He’s not sleeping, he’s watching TV instead.

The ‘weirdest construction’ is similar, but it says that the first (negated part) is an understatement. An example in English would be:

I’m not (just) cold, I’m (actually) freezing!

And in Croatian, it looks like this:

Ne da mi je hladno, nego se smrzavam.

What is ‘weird’ in this construction? First, ne¨ and da are glued into a complex conjunction (still spelled as two words, of course, but usually pronounced as one word). You can’t place anything in between. The conjunction (or whatever it is) nego is optional:

Ne da mi je hladno, smrzavam se.

The second weird thing is that you can pull things (I mean, words) out from the da clause:

Meni ne da je hladno, nego se smrzavam. (the same meaning, emphasis on the person who feels it)

Pulling subjects out is quite common (but optional):

Voda ne da curi, nego tečeteći. Water is not just leaking, it’s flowing.

The understatement in the first part can be also negative:

Ne da nije pročitao knjigu, nije ju ni otvorio. It’s not just that he didn’t read the book completely, he didn’t even open it.

The English translation is not so elegant, but it’s a very compact expression in Croatian.

Pulling words out of clauses is possible for other types of clauses as well (recall the example in chapter 63 Bigger and Better: Comparatives). This is less common than using clauses with all words in them, but you’ll see often pronouns being pulled out:

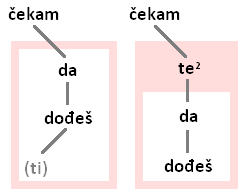

Čekam ga. I’m waiting for him.

Čekam [da (on) dođedoći]. I’m waiting for [him to come].

Čekam ga [da dođedoći]. (the same meaning, the pronoun pulled out)

As you can see, the last sentence has a structure very similar to the English sentence, but the verb is still in the 3rd person. The pulled out pronoun isn’t ‘hidden’ in the clause anymore, and since it’s a part of the object of the verb čekati wait, it must be in A. Also, the clause can’t be moved around.

Pulling words out of clauses is not that common: if you Google™ for "čekam te da dođeš" and then "čekam da dođeš", you’ll get results in big favor of unpulled pronouns (about 10:1) – but be prepared to see and hear such a thing from time to time.

________

® In most of Bosnia, instead of prošli tjedan last week, prošle nedjelje is used; in Serbia it’s in the “Ekavian” form prošle nedelje.

In Serbia, besides osim, the word sem is also used, with the exactly same meaning and grammatical properties.

No comments:

Post a Comment